Dalit art evolved as a mode of resistance and protest. It tires to historically trace the origin and the seriousness of caste discrimination from the past till present. Dalit artists across India have picked up themes, which invoke a deep sense of contemplation in the minds of the onlooker. Dalit art is a representation of critical issues of domination, discrimination, and oppression encompassing along the triple oppression faced by Dalit woman. Dalit women’s problems encompass not only gender and economic deprivation but also discrimination associated with religion, caste and untouchability which in turn results in the denial of their social, economic, cultural and political rights, One such artist from Maharashtra named Savindra Savi has successfully done so, through his art he has a created a mode of protest and also tries to track the interplay between meaning and power within hierarchical structures of religion, caste, gender, and politics.

As Y.S. Alone puts it, Dalit art needs to create a social space for itself, which is associated with hegemony and monopoly. The native hegemony of dominant castes. Adherence to social reality in the pictorial space was a major shift affected by Indian Painters. They succeeded in legitimizing their own culture and social environment through their art practice.

As Gopal Guru aptly explains that the evolution of Dalit art varying from folklores to paintings to folk poetry has provided Dalit’s with an intellectual platform for creation as well as articulation for laboring Dalit’s women self perception of emancipation. He very well states that Dalit emancipation is not only possible through government policies as they are temporal in nature but through cultural and intellectual stimulation which will create a language of resistance and fully loaded with meanings and have a story of their subordination and suppression.

Evolution of Dalit style of Mithila Paintings

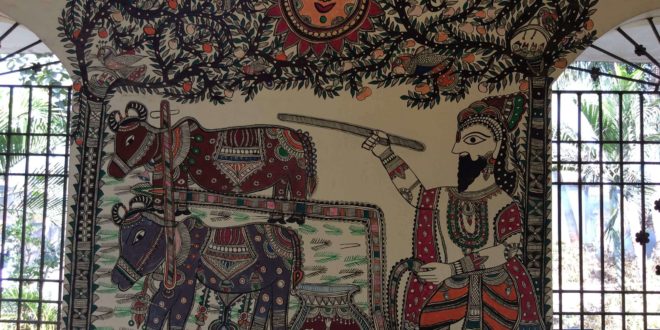

In the region of Mithila, there were particularly women from two sub-castes among the Dalit community had mastered the art of Mithila painting which was different from paintings by an upper castes women. These women belonging to Dusadh and Chamar community had developed their own distinct style of paintings and various new themes were included. The credit to Dalit inclusion in Mithila Paintings goes to a German anthropologist, Erika Moser, having inspired and guided Dusadh women back in 1978 to embrace the art and start writing a new chapter of their social recognition and economic independence. The German anthropologist film-maker and social activist Erika Moser persuaded the impoverished Dusadh community to paint. The result was the Dusadh captured their oral history (such as the adventures of Raja Salhesh, and depictions of their primary deity, Rahu) — typified by bold compositions and figures based on traditional tattoo patterns called Godna locally. This added another distinctive new style to the region’s flourishing art scene. With the financial support of Moser and Raymond Lee Owens along with land in Jitwarpur donated by Anthropologist Erika Moser, the likes of Dr. Gauri Mishra spearheaded the setting up of the Master Craftsmen Association of Mithila in 1977. This association was very active during the lifetime of Owens and worked in tandem with Ethnic Arts Foundation of USA.

Dusadh women were very receptive to her ideas of starting a profession in Mithila Paintings but at the same time were apprehensive of their awareness and strength against the much-established Brahmin women leading the art. These apprehensions were born around the lack of their knowledge for elaborated painting styles like Kohbhar and Aripana, Hindu customs, deities, Gods and goddesses over which the Brahmins has created a complete dominance and epics like Ramayana and Mahabharata making them doubt their ability to translate the same on paper in form of beautiful paintings with meaningful message. Erika Moser guided these women to rather focus on their own rich customs and folklore, their own deities and idols, culture and rituals instead of high Hindu castes and paint in their own thematic style.

Empowered by the words of an educated European woman and her other operational help, Dusadh women started to embark on their own journey of Mithila paintings and its rewarding experience. In coming days this art and its practice would give a lot of confidence to hitherto downtrodden members of Dusadh community raising their self-esteem to participate in more empowering political movements and discourses. Thanks to their political mobilization and social awareness, Dusadh community today is an active force in Mithila and Bihar Due to unfortunate absence of Dusadh paintings in photograph collections of William Archer and his wife Mildred, the available account of it comes from various short films by Erika Moser in 1970 and few photographs by Mary Lanius. In 1980, Given their technical constraints of painting on mud or cow dung plastered walls, Dusadh paintings, to some extent have a similarity with that from Brahmins and Kayastha, however, they were immediately distinguishable from more popular kachni and bharni paintings of the same era. Dusadh women in this period mainly painted trees, creepers, flowers, and molded low relief clay figures of deities and animals on external walls of their homes. Dusadh women created three major distinct painting style and techniques. The most popular and important one among these is the tattoo style paintings or Godana on limbs and chest of people. They include an auspicious and protective image on the human body mostly having rows and concentric circles of flowers, fields’ animals and deities done initially by bamboo pen and lampblack ink. Many painters emulated this form of paintings and very soon tattooed paintings started to proliferate in this region. People started to use bamboo pens and gradually started using organic colors as well made from flowers, grains, harvest, turmeric etc. As Dusadh women started to use colors in their paintings, their scope of content and subjects to make their paintings also increased significantly. They now started to include other gods and goddesses like Suriya (the sun goddess), their cultural hero Raja Salheshand his adventurous escapades, the tree of life, and Rahu. Though these paintings used colors and broads elements they substantially differed from existing Bharni and kachni paintings of that time. The second form of paintings was innovated by Jamuna Devi, a local woman belonging to Chamar caste, and was somewhat similar to bharni paintings. They abundantly used natural and synthetic colors besides using large images of deities, gods, human beings and other anthropomorphic forms. However, these paintings were distinguished by bharni paintings by the use of a double line of cow dung and lampblack dots between the lines and other places around depicted figures.

Follow The Charticle on Facebook: @thecharticle

One additional form of paintings was also innovated by Jamuna Devi when she started washing the paper with cow dung to give it a sullying texture and appearance. Initially, the idea of washing the drawing paper with cow dung dint go quite well with the artist community but the inspiring response from the market and huge subsequent demand for same established the use of cow dung washed papers as a mark of superior paintings imbibed by Brahmin and Kayastha women as well. Eventually the papers which were smeared by cow dung became very popular among the people and the artists began artists such as called Siban Paswan and Rajesh Paswan from Jitwarpur does that very frequently creating a distinct style of coloring for themselves, the smearing of paper gives it a distinct smell when it is fresh and adds an earthly hue to the paper making it more visually appealing.

Geru Paintings

Geru (brown) included big figures of gods and goddess, animals and fields largely painted in light brown along with few more bright color objects on the paper. Resembling low relief figures on the walls of homes of Mithila inhabitants, these paintings dint take off too well and couldn’t attract many buyers. The fact to ponder upon here is that none of these Dusadh paintings or High caste paintings from Brahmins and kayastha women has remained stagnant from the times of their inception to today. Mithila Art is under a state of constant evolution and also intermixing of styles among its subcategories. That is to say, not only the theme of Bharni Paintings or Kachni Paintings has changed slightly over time but also elements of Dusadh Paintings have penetrated in the same. This could be studied by taking examples of Brahmin painters who now abundantly use cow dung wash papers to add sullying beauty to their bharni paintings and the Dalit painters who use a lot of colors and broad figures in their paintings resembling bharni Style and often depicting kohbhar images also in their creations. The art of Mithila Painting has facilitated an exchange of quality styles among the artists of all castes and aesthetic signs of one could be well appreciated in the other. This being said the overall ambit of Mithila Painting includes paintings with some distinct broad identifiers like the repeated image of the subject of the painting, Single plain, no use of perspective or shading, full face representation of gods and goddesses. The skills of Dusadh painters increased manifolds in around last 4 decades.

Now they are not only drawing images of Shiva and Krishna but also expanding their content base. They are depicting the adventures of Raja Salhesh, Rahu (Dusadh community Sun God), besides current social and rural life issues to give a contemporary appeal to their work. One major element of their paintings is the life tree, a huge tree with images of animals, flowers, regular day-to-day household items, gods and human forms in various stages young to old etc. These trees of life have been thoughtfully used by Dusadh painters to depict intellectually stimulating concepts of cosmological inference such as Raas to a more regular depiction of the nomadic journey of migrant workers assembling in Jitwarpur and nearby areas during the harvest time in order to find work. Though upper caste painters have used small trees, leaves and other related images repetitively as fillers in their paintings; they haven’t been very explicit and thought to apply with the tree of life which is popular in India and Europe.

Gobar Style

This style of Painting was started by Jamuna Devi, by basically giving the paper a light Gobar (Cow dung slurry) wash to give it a beautiful sullying look and feel on which bright colors often come out very beautifully. From the caste perspective, it’s important to note that unlike other scheduled castes of Jitwarpur village like the Malis, the Pasis, Doms, and Dhobiwho all stuck to their traditional professions, the Chamars and the Dusadhs have forayed into a full-time profession of Mithila Painting. At this point, it’s helpful to probe the socioeconomic background and status of these two castes before studying the evolution of their art and its modern significance. Even today these castes The Chamars and The Dusadhs by a majority of residents in the same region are considered inferiors and untouchables and discriminated openly in social transactions and exchanges. There are various sources and studies done on history and background of these castes at the bottom of the pyramid and they unanimously bring forth the plight of being a low born by birth. Dusadhs and Chamars are among the most devoid of castes and denied the basic human rights. These included restriction on them using the village well, expected to not cross high borns daytime during their walks in fields and villages, couldn’t eat or participate in village social affair, feasts and gatherings and most primitively above all “ cast of impurity on a higher caste person if a Dalit’s shadow falls on him or her. Neel Rekha a renowned sociologist in her article ‘Salhesa iconography in Madhubani Paintings: A case of Harijan assertion’ throws light on this “ Mithila was basically an agricultural economy. The feudalistic pattern of society and economy, which originated in the pre-medieval Mithila, continued till the present century and only a small section of Maithil Population was economically well off on account of either education or through the landed property. With the region witnessing a series of droughts in the 50’s and 60’s, the meager income derived from agriculture also came to an end. It resulted in a large-scale exodus of men and women belonging to the lower caste communities to the cities. Many painters from the Dusadh caste of Jitwarpur revealed that they were earning their living by pulling rickshaws in Madhubani.

The Chamars, also known as Ravidas, were by occupation makers of footwear, cultivators or laborers. Their traditional occupation was the disposal of dead animals and to prepare different objects out of the skin of dead animals. Their caste occupation also included dealing in other objects obtained from the body of dead animals such as horns, bones, and flesh. However, their main work was the processing of skin and making of footwear. Even today in some villages, they still have the right to the hides of the dead livestock. In the past, they were often suspected of poisoning the cattle. The Dusadhs were one of the useful castes in the area owing to their value as agricultural laborers. They reared cattle, pigs etc. and supported themselves mostly by labor and cultivation. They also monopolized the post of village chowkidars or watchmen in the district.

of the titles among the Dusadhs was Paswan, which means a watchman or a guard. Their women supplemented the income of the family by working as laborers. The Dusadhs were enlisted among the criminal castes of the district. Poverty and social incompatibility seemed to be the immediate environmental factors responsible for leading to criminal acts “ The scheduled castes also from an early time had the culture of decorating their houses, kothis, storage other broad surfaces with figures of animals like horses and elephants but these were simple images devoid of any aesthetic or ornamental qualities. Making mud wall frescoes was very popular with them. However, the growing popularity of Brahmanical and Kayastha Paintings more precisely known as Bharni and Kachni, started to inspire lower caste Dusadhs and Chamar women as well and they wanted to learn the art behind these paintings. This was however not easy as Dalit Painters devoid of any knowledge of rich and ornamental Brahamanical or high caste rituals, deities, and gods; found themselves clueless about imitating Bharni and kachni painting styles.

Follow The Charticle on Twitter: @thecharticle

Lower caste women mostly caught in village hard physical work and domestic chores had little awareness of accounts of uncountable Hindu gods and deities and expecting guiding hand and time from their high caste counterpart women seemed difficult owing to social differences. This is where the motivation and skill specific advisory from the likes of Bhaskar Kulkarni, Raymond Lee Owens, an American anthropologist, and Erika Moser, a German folklorist comes as a savior for the evolution of Dalit Paintings in its current form. Bhaskar Kulkarni gave Jamuna Devi, one of the first Harijan women to start commercialized painting, the idea to wash the drawing paper with a light Gobar wash thus laying the foundation for Gobar or Geru Paintings. Jamuna Devi thus started a new and distinctive style of painting, which in coming times attain huge recognition and demand in commercial markets besides being emulated by painters from upper caste as well. Holi colors on cow- dung paper imparted an unusual brightness to her paintings making Jamuna Devi shot into prominence with her mud frescos and paintings reserving a place in big exhibitions of Japan, New Delhi, Patna, and Varanasi. Roudi Paswan, Jitwarpur husband of artist Chano Devi played a significant role in the evolution of Godana paintings. Introduction of natural colors, stories of local deities such as Rahu, Govinda and Salhes, Gobar style, tattoo motifs and contemporary themes by the Dusadhs gave a huge distinctive appeal and beauty to. Men from the region were also instrumental in helping women folks to produce the masterpieces. Ramvilas Paswan from village Laheriagunj and Roudi Paswan of village Jitwarpur were forces behind these innovations in Dalit paintings. Their occupation as the local priests of the Dusadhs helped Dalit women get a hang of their own cultural history and know the gods like Salhesa and Rahu better. Another pioneer credited with popularizing community legends in Dalit Paintings was Shanti Devi who learned the art from her mother- in -law Kushuma Devi. She worked her husband Seewan and they were inspired by the efforts of Raymond Lee Owens urging them to depict legends from their own community into their paintings. She was distinctive from Jamuna Devi in the manner of making large panels with natural colors in Gobar outlines. Another major form of Dalit Paintings to mention here are Godana paintings by pioneered by Chano Devi the wife of Roudi Paswan’s. Eric Moser saw tattoos on Chano’s body and suggested her to get the tattoos on paper. Her partner in evolving this style of paintings was Palti Devi – a Natin who had performed these tattoos on Chano’s body. They worked together in isolation of a mango grove for two months and evolved this new painting style.

Godna art

Evolution of Tattoo Paintings can be traced back by studying the ritual and habits of Nat Community. Natins, the women folks of this community have been master tattooers since a long time. Dalit women from Bihar have used Godna as an idiom to make an elevated sense of Dalit emancipation, which they explain in terms of the annihilation of caste and the restoration of manuski [dignity to themselves]. Gopal Guru in his work draws light towards intellectual expression in forms of work undertaken or forced on Dalit women. The nature of work remains demeaning and is further trivialized by the internal paradox of a patriarchal Dalit imagination. The hierarchical space within which Dalit women worked, has also been the sight of ‘distinctive subjectivities’ that women expressed in response to the nature of the work. Guru opines that Dalit women have been expressive and created their own forms of deliberation in response to the exploitative conditions of work imposed upon them. He categorises Dalit women into two, first the ones who are involved in a particular kind of labour that helps them to articulate through forms such as paintings, tattoos and folk poetry and relate to Ambedkar and the second category of women which do not have any formal education seem to resonate with his ideology and become a voice in articulating to Ambedkar’s recourse on the basis of trust. Example Guru highlights how women self-assertion came through unmediated language with a sense of individual creativity and purely through experience in the field of work. Gopal guru illustrates the ways in which women deliberate a feminist articulation situated in a particular kind of work. Taking the case of Godna Painting, Dalit women in the Madhubani district of Bihar express their pain through the idiom of Godna to Dalit emancipation, which they explain in ‘annihilation of caste and restoration of mansuki (Dignity to themselves). Godna originally meaning the art of tattooing was adopted particularly in the provinces in Bihar and Bengal, to imprint the prisoners as well as demonstrate an upper caste distinction. Historian Claire Anderson, researched and claimed that most of these tattoos were made by lower caste illiterate women who use to draw creative patterns and number on upper caste bodies, ordered by the imperial authorities. However, the history Godna lies in the discrimination suffered by the Dalit women when they were forced to wear ornaments of iron and inferior materials as prescribed by the Manu code. Tattooing was thus seen as an inversion of that prescription that marked distinction from the lower caste in the public. Godna, was not only seen as the inversion of markers of identification for the Dalit women but was also viewed as an attractive alternative to forms of subaltern expression for these women. Guru opines that the form of deliberation has considerably shifted from ‘body as being the base for cultural imagination’ with decorative tattooing to penal tattooing to a gradual shift to paintings on Ambedkar on paper. Even though this recent form of intellectualism is appreciated for a more institutionalized grounding and visible recognition, what remains a pertinent concern is the fading away of such subaltern intellectualism, like the practice of Godna art conveying a vital form of expression among the subaltern women laborers. The small size of the Godana images made them popular with Textile designers and they started to be a popular marketing advantage for the textile industry. Godana paintings started dominating the Marketing field. The early designs of tattoo paintings were simple black & white figure like the way on human bodies and they mostly revolved around auspicious image and onuses thought to be lucky in Nat Community. However overall these tattoo paintings did not carry deep meaning or storytelling within them. This is where the contribution of Chano Devi, the early star of Godan (Tattoo) Paintings is remarkable. Under her husband’s guidance, she started depicting the life histories of Salhesa to add meanings to the tattooShanti and Chano Devi also started to experiment with natural colors in order to create more distinctive style. These colors later became the main identifier of Dalit Godana paintings. Falling in line other painters started to abandon the use of Holi colors in favor of natural colors and thus a new full-fledged style of Colorful Godana (tattoo) paintings came into limelight. These natural colors mostly came from cow-dung base and leaves, flowers, vegetables, barks, and roots. The journey of Dalit Paintings from Gobar Paintings to the Godana Paintings finally established Dusadhs and Chamar Caste women in the field of folk art. Dalits started from imbibing early popular high caste painting style and themes focusing on Stories of Rama, Sita, Krishna, and other Hindu legends. However, not only Dalit Painters were less versed with these elaborate Hindu rituals and thus ordinary translators of same on their paintings; they also were only seen as followers of already established trends. There was definitely a need for original style creation from Dalits to put them in the league of High caste Brahmins and Kayastha women who were reputed to be the creator of the art.

There was a need for Dalit owned story and elaboration of their own culture on painting papers. The depiction of God Salhesa in Dalit paintings, thus giving it a major shift from ongoing paintings on day-to-day life, nature, and chores of Dalit women, marked the beginning of Dalit Clout in the world of Mithila Paintings. A new style was born and this time in the humble homes of The Dalits. An analysis of Shanti Devi’s (The pioneer of Dalit paintings besides Channo Devi and Jamuna Devi) work reveals that Govinda, A god for Halwais also remained her favorite besides Salhesa. It is also to be noted that the number of Dusadh painters eventually outnumbered other scheduled castes especially the Chamars who came even before them. The followership of Salhesa Paintings among the artists as well as the market made it the most popular theme under the overall category of Dalit Paintings and Salhesa was chosen to represent all the scheduled castes.

Evolution of Dalit art came as a mode of resistance as it is evident, it marks the creation of social space for themselves in the cultural hierarchy of the society. Dulari Devi, Rajesh Paswan, Shivan Paswan, Channu Devi, and Roudi Paswan are some of the individuals who despite belonging to the low caste did work for their cultural upliftment and are successful to a greater extent. In the contemporary era, Godana paintings are very famous and popular in the market but due to consumer demand and the paintings have become highly commercialized we see an intermixing of Godana art with other styles of Mithila paintings which are a deviation from their original art form since its inception. Among the Dalits in Bihar Dusadhs and Chamar have led the way in evolving their own style of painting and asserting their identity by creating their social space.

– By Aditi Narayani, Aditi is a Research Scholar at Centre for the Study of Discrimination and Exclusion, JNU.

*Some of these aspects at length and in detail have been covered in M.Phil. Dissertation entitled “Folk Art of Mithila: Understanding Paintings and its Intersectionalities”, submitted to Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, in 2017*

The Charticle Asia's top notch digital journalism

The Charticle Asia's top notch digital journalism